How to Fit a Shower Tray

Overview

Let’s face it. Showers are the bathing choice of just about everyone. So if your bathroom has become a family bottleneck because you don’t have enough shower stalls or the one you have is leaking, read on. We’ll show you how to replace a leaky base, replace a tub with a shower only or install an additional shower to handle demand. Preformed shower bases have vastly simplified the installation process. They’re virtually leakproof and are vastly easier to install than traditional solid mortar bases.

Still, setting a base can be challenging, especially when you’re remodeling older plumbing. In this article, we’ll show you how to rip out an old tub and replace it with a one-piece fiberglass shower base. We’ll walk you through the tricky parts, first how to relocate the drain just right, then the necessary venting. Next, we’ll show how to set a rock-solid base—one that won’t crack or leak down the road. Our step-by- step instructions will take you right up to the point where the walls are ready to finish. But we won’t go into those finish details here.

This is mostly a plumbing project. To take it on, you should be familiar with basic pipe joining techniques. Mostly this involves cutting and cementing plastic pipes and fittings. Don’t worry if you make mistakes. The materials are inexpensive and corrections are easily made by cutting out sections and installing new fittings and pipes.

Completing this job—getting the old tub out, reworking the plumbing and installing the new base—will take a Saturday at least, a weekend at most. If you have to run a drain line through joists or studs, we recommend that you rent a 1/2-in. right-angle drill and a 2-in. hole saw (or bit; Photo 6). Otherwise basic plumbing tools and hand tools are all you’ll need. Be sure to apply for a plumbing permit and have an inspection done at the rough-in stage (when everything is still exposed) and after everything is complete (wall surfaces finished, final hardware installed).

Step 1: Planning the job

Start by deciding on the size of the shower base and ordering it. Delivery can take weeks, so don’t rip anything apart until the new one is in hand. If you’re replacing an existing base, simply get one the same size. If you’re replacing a tub with a shower as we did, there are more details to consider. You’ll have the fewest problems if you match the new base to the old tub’s width (the front of the tub to the wall). Go wider if you like, but you may have to replace flooring. Or you may overstep required minimum distances from toilets and sinks. You might have to shift the supply valve as well. Keeping the same tub footprint (or smaller) minimizes the hassles.

We replaced a 5-ft. tub with a fairly spacious 4-ft. base the same width as the tub. (See “Selecting a Shower Base,” below.) We framed a 1-ft.-wide filler wall at the end, which is a nice place to build recessed niches and shelves for shower supplies.

Now’s a good time to buy a new shower valve too, especially if your old one doesn’t have scald protection, as all new ones do. It’s a big project to replace a valve that fails after tile or wall panels are installed.

You’ll need an assortment of pipes and fittings for installing the new drain and for reworking water lines. Pick them up after you open up the floor and walls. At that point you can see what you need, plan the new drain and water supply runs and make a list of supplies. Make a sketch like Figure A to help you keep track of parts.

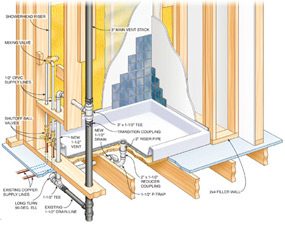

Figure A: Shower Base/Drain Details

Make a sketch of the project that includes the waste, vent and water supply. Drawing the details will help avoid potential problems and also reduce the number of trips to the hardware store.

Shower base and drain details

Shower base and drain detailsStep 2: Remove the old surround and tub

Photo 1: Remove the wall

Remove the faucet valve handles and escutcheons. Cut through the drywall that surrounds the tile with a utility knife and pull chunks from the wall.

Photo 2: Disconnect the plumbing

Shut off the main water supply valve. Cut out the water supply lines and install ball valves if you don’t already have them.

Photo 3: Remove the tub

Disconnect the trap from the tub drain, then lift the tub free from the wall and carry it out.

First unscrew the showerhead and the bathtub spout. Most styles will unscrew, but some will need persuasion with a pipe wrench. If you want to reuse any parts, wrap the tool jaws with cloth to prevent damage. Then remove the handle and mixing valve escutcheon cover. Most handles have a little plastic cap that pops off to expose a screw. Remove the screws and pull off the handle and the escutcheon.

Next, strip off the tub surround. Begin by cutting completely through the drywall around the perimeter with a utility knife. If you have cement board behind the tile, simply cut through the tape joint at the ceiling and strip the entire wall. Rip off the tile and drywall together in big chunks (Photo 1). If you have a fiberglass surround with a flange behind the drywall, cut 2 in. outside of the enclosure and pry the sections free one at a time.

With the wall open, disconnect the plumbing. Usually you can access the trap from an access panel in the room behind the tub or from an unfinished basement. If you don’t have access, you’ll have to cut a hole in the wall from behind the tub base. If your shutoff valves are in good shape, cut off the water lines above them. If they’re missing, stuck or corroded, shut off the main supply valve, cut off the water lines and install two compression fitting–style ball valves and leave them in the closed position so you can turn the water back on to the rest of the house (Photo 2). Cover the ends with tape to keep out debris.

Fiberglass and steel tubs are fairly light; you can just tip them up and carry them away (Photo 3). If framing makes it difficult to pull out, cut out more drywall along the plumbing wall. Then you can pull the tub away from the wall before you tip it up. Cast iron tubs, on the other hand, are extremely heavy, and we recommend just busting them up with a sledgehammer and carrying out the pieces. (Lay an old blanket over the tub to catch flying shards, and wear safety glasses for this!)

Step 3: Mark the exact drain location and open up the floor

Photo 5: Cut an access slot

Mark and cut an access slot in the subfloor for roughing in the new P-trap and drain line. Cut over the center of joists where possible.

Snug the new shower base up to the wall studs and mark the drain hole (Photo 4). Then pull it aside and draw an access slot on the subfloor (Photo 5). Make the slot about a foot wide and extend it just beyond the new drain location. Keep the edges of the slot over the middle of joists wherever you can to make patching easier later. Make reference marks on the floor outside the slot so you can relocate the center of the drain once you remove the flooring (Photo 6). Pull any nails that fall within the cutting lines. Then set your blade depth to cut just through the subfloor, make the cut and pry it free (Photo 5).

Step 4: Rough in the drain and vent lines

Photo 6: Cut a path for the drain

Drill 2-in. holes through the floor joists for the new drain line. Reference marks help you find the drain center later.

Photo 7: Install the sanitary tee

Cement 6-in.-long nipples to both ends of a 3 x 1-1/2-in. sanitary tee, then mark and cut the main stack. Join it to the stack with transition couplings.

Photo 8: Run the vent

Drill 2-in. holes through the studs, sloping away from the tee 1/4 in. for every 1 ft. of run.

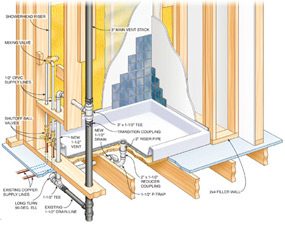

Photo 9: Dry-fit the waste and vent

Dry-fit the new vent line and drain line fittings, working your way toward the P-trap. Use reference marks on the subfloor to fine-tune the location of the drain.

With the floor and wall open, you can plan your new drain and vent lines. Reworking drain and vent lines will be slightly different with every bathroom, but our photos and Figure A will give you the general idea along with a look at the various fittings you may need.

If your tub didn’t have a vent, you’ll probably have to add one. A local plumbing inspector will tell you the rules (usually within 42 in. of the shower P-trap) when you apply for a permit. The new vent must join the main vent at least 6 in. above any “spill lines” (that usually means sink rims) that share the vent. You’ll probably have to open a wall to get it in (Photos 7 and 8).

The two keys for adding a drain are to make sure the horizontal lines slope 1/4 in. for every running foot and that the P-trap opening falls directlybelow the shower drain hole. Start by measuring the height of the center of the existing drain line and the distance to the new drain. Cut off the old P-trap, then run the drain line to the new drain location (Photos 6 and 9). Remember to allow 1/4-in.-per-foot slope when you drill holes in joists. Drill 2-in. holes to leave some room to move the 1-1/2-in. pipe up or down to get the necessary slope. But don’t drill in the lower or upper 2 in. of any joist. Most shower drains are designed to receive 2-in. piping, while most existing tub drains are 1-1/2 in. The plumbing code calls for the transition to be made with a reducer directly below the shower (Photo 10), nowhere else.

To run the new vent, mark a section of main stack for removal using the 3 x 1-1/2-in. tee (with 6-in.-long nipples) as a guide (Photos 7 and 8 and Figure A). If your main stack will be plastic, cutting it is easy with a hand or reciprocating saw with an 8-in. blade. If you have cast iron, you’ll have to rent a pipe snapper to make the cut. Slip the fitting into the opening and secure it with transition couplings. Then run the vent line down to the drain, cutting holes in the framing as needed. Horizontal sections should also follow the 1/4-in.-slope rule, running downhill toward the drain. Cut all the pipes and dry-fit them one at a time to the fittings, then double-check the drain line slopes and final drain position. Set the shower base in place to double-check the final placement of the P-trap, inserting a short, temporary tailpiece (Photo 9). When you set the shower base permanently, measure and cut a permanent tailpiece and cement it into place.

Starting at the main vent and working toward the P-trap, begin cementing the parts together. If you’re using PVC, hold the parts together for about 20 seconds after cementing. Otherwise, the parts will “squirt” apart before the solvent cures. Save the P-trap-to-drain-line connection for last. Cement it together, and quickly plumb the P-trap with a 6-in. level before the joint sets (Photo 9). Your building inspector will want to see the drain and vent (and possibly the water supply rough-in; Photo 11) before you close up the floor.

Step 5: Patch the floor

Photo 10: Close the floor

Add blocking to shore up the subfloor and screw a patch to the framing with 1-5/8-in. screws. Add a second layer of 1/2-in. subfloor if your finished floor covering will permit it.

Add blocking to bolster unsupported plywood edges and screw a patch to the framing with 1-5/8-in. screws (Photo 10). We added a second layer of 1/2-in. underlayment under the entire shower for a sturdier floor and to better match the finished floor height (1/2-in. backer board and tile). If you need to preserve the original floor height, skip the second layer, but add blocking under the single-layer patch to fully support the shower base.

Selecting a Shower Base

You won’t be able to enter a home center and walk out with a 4-ft.-long shower base like the one we show. Ask to go through the plumbing fixture books there to special-order one that suits your bath decor and budget. Some come with drain adapters, as ours did. You’ll have to check, and purchase a separate shower drain kit if needed. The manufacturer’s directions will help you choose the right one.

There is another (but more costly) option if you’d like to skip all of the extra venting and drain work. Select a shower base that has the drain located at one end, right or left, chosen to match your old tub drain. Select one the same length as the tub and you won’t even need to add filler walls. Since the drain position roughly matches the tub drain, you may not have to add a separate vent, cut out and patch the floor, or reroute the drain line.

Shower base

Shower baseStep 6: Mount the mixing valve and redo the supply lines

Photo 11: Run new supply lines

Mount a new mixing valve and run new CPVC or copper tubing from the ball valve to the mixing valve and showerhead. Cap the tub spout outlet on the underside of the mixing valve. Turn on the water and check for leaks.

Unless you’re planning to reuse all of the existing supply lines and valves, simply cut out and remove everything and start fresh. Use a hacksaw or a reciprocating saw.

If you’ve chosen a shower base that’s wider than the tub, center the new mixing valve and showerhead over the base. Choose a valve height that’s comfortable to reach and clears any obstacles, and make sure the showerhead lands either above or below the top edge of the shower enclosure or tile. Mount the mixing valve first, following the manufacturer’s instructions, and then fill in the pipes and fittings to and from it (Photo 11). You’ll need to add blocking to support it.

There may be a threaded nipple or hole in the bottom of the mixing valve for a tub spout. Be sure to cap that. After everything is together, shut off the mixing valve, turn on the water and check for leaks.

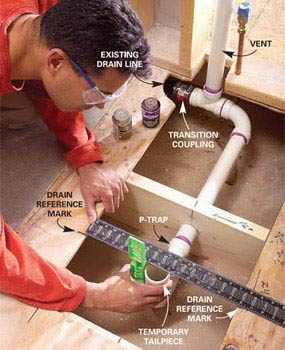

Step 7: Level the base and mark the studs

Photo 12: Position the base

Level the shower base on all four edges, shimming where needed. Mark the lip where it abuts studs. Measure, cut and cement the final tailpiece to the P-trap.

Photo 13: Set the base in mortar

Spread mortar under the base. Push the base into the mortar until it rests on the shims and aligns with the stud marks. Let the mortar harden.

Photo 12 shows you how to dry-fit, level and shim the shower base. Take your time. Getting the base level is critical for good drainage. Mark the lip height on the studs and outline the shim locations so you can lift out the base and return it to the exact position. Some bases require that you fit it over a tailpiece when you set it in mortar.

To set the base, mix up about half a 60-lb. bag of mortar with water to a creamy consistency. Avoid concrete mix; stones in the mix will hold the base away from the floor. Spread the mortar over the floor under the base, about 1 in. or so thick. Then lower the base into the wet mix, forcing it down to the shims and the stud marks. Make sure to push it against the wall. Let it cure overnight. Don’t use the base as a work platform until the next day or you’ll disturb the mortar before it cures. Clamp the base lip to each stud if clamps are included with the unit. Otherwise, clamp it with fender washers and 2-in. screws. Avoid drilling through the lip and screwing the base directly to the studs. The base might crack and leak.

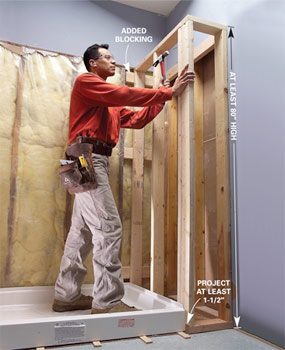

Step 8: Attach the drain and frame the end wall

Photo 14: Complete the drain hookup

Anchor the base to the studs with screws and washers. Push the rubber gasket into place and seat it with a nut driver.

Photo 15: Complete the framing

Frame the end wall at least 80 in. high for shower doors and curtain rods.

The base will have directions to guide you through the final drain hookup; your drain system may vary from ours. Cut the tailpiece and cement it at the right height. If your drain has a thick rubber gasket, wet it with soapy water and then work it around the tailpiece pipe. Finish seating it by driving it down with a blunt tool.

Our base was shorter than the old tub, leaving a void between the wall and the base. We filled in the space with a 2×4 wall. Add backing where the new walls meet existing ones to make the connection solid and for anchoring backer board. And if you leave it short of the ceiling as we did, you can add a convenient built-in shelf.

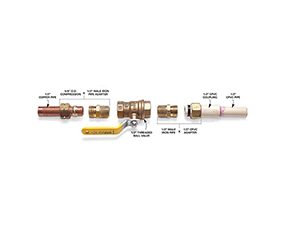

Copper vs. CPVC

If you’re comfortable working with and soldering copper, by all means go ahead and use it for your water supply lines. We show CPVC plastic fittings because the installation is as simple as cutting and cementing plastic fittings, just as you do with plastic drain and vent lines. To make the transition from copper to CPVC, use compression fittings as shown. You’ll find all the CPVC fittings and pipes you need at any hardware store or home center.

Copper to CPVC transition

Copper to CPVC transitionRequired Tools for this Project

Have the necessary tools for this DIY project lined up before you start—you’ll save time and frustration.

Tube cutter, Utility knifeRequired Materials for this Project

Avoid last-minute shopping trips by having all your materials ready ahead of time. Here’s a list.

Comments

Post a Comment